How Savile Row Became The World’s Leading Tailoring Destination

The Japanese take their word for a suit, “sabburu”, from its name. Savile Row has come to be regarded as the epicentre of world-class tailoring. Other places can cut a good suit: Hong Kong and Shanghai if you need speed, New York if you need swagger. Indeed, tailoring is not quintessentially British – it probably originated in Medieval France, “tailor” derived from “tailler”, meaning to cut. But no other place has been so intimately associated with the craft of cutting, shaping and stitching. A small strip of west London – a back road you can see end to end and named after Lady Dorothy Savile, the wife of Earl Burlington, the area’s one-time owner – has become home of the suit.

It was one Robert Baker – the man who created Piccadilly, itself derived from pickadil, the name given to Elizabethan shirt collars – who arrived in the area during the late 1500s to set up its first tailoring business, one so successful that he was appointed suitmaker to the court of James 1. Looking around now, he might feel a little dismayed. It is proving increasingly hard to encourage young people, in their teenage years ideally, to train all hours for years and a pittance for a craft that will earn them a tidy, but not liberal income and a life in a strip-lit basement. The glossy allure of designerdom, the fame and flash bulbs at the flash parties, seems a much more attractive route into the fashion industry.

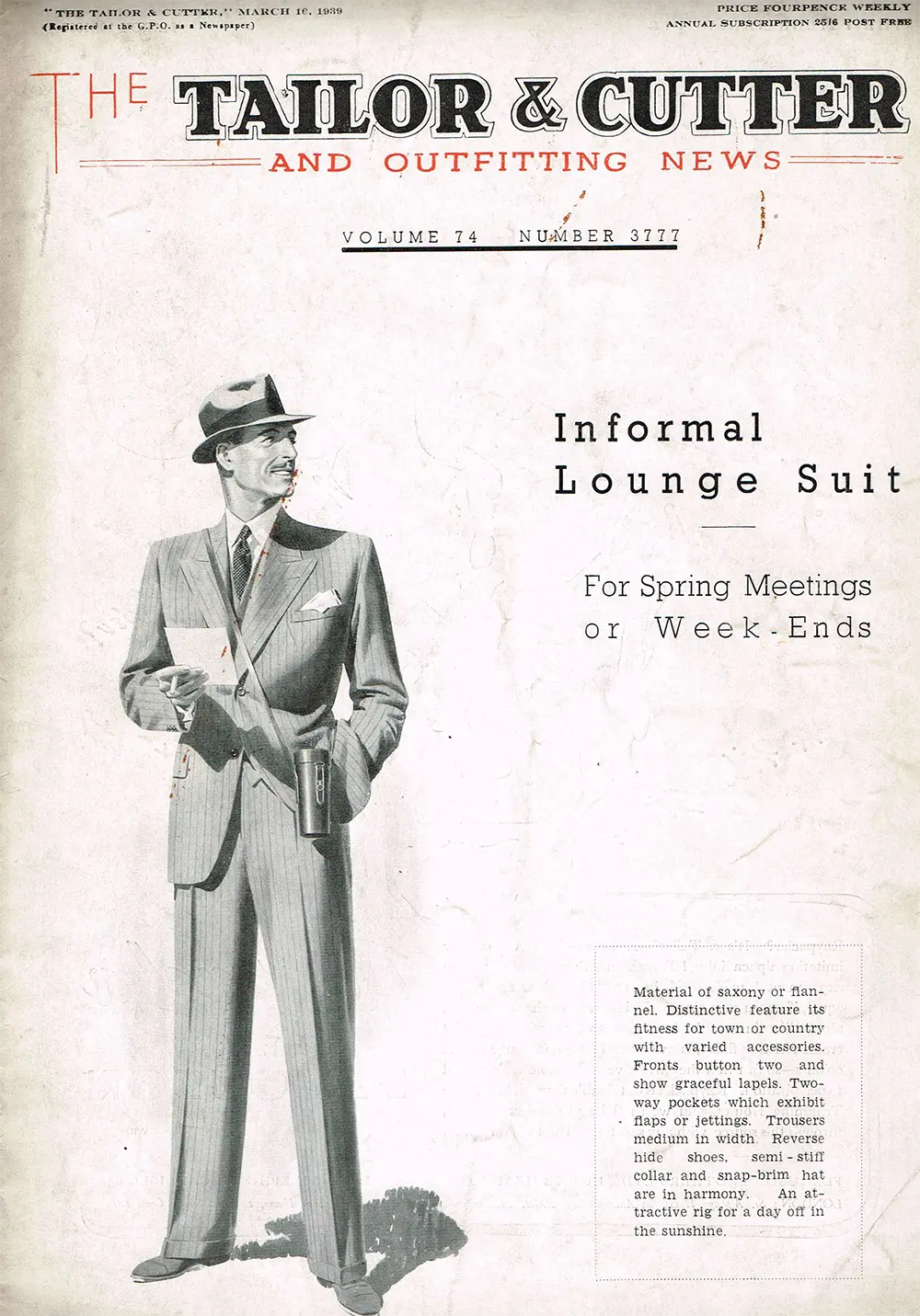

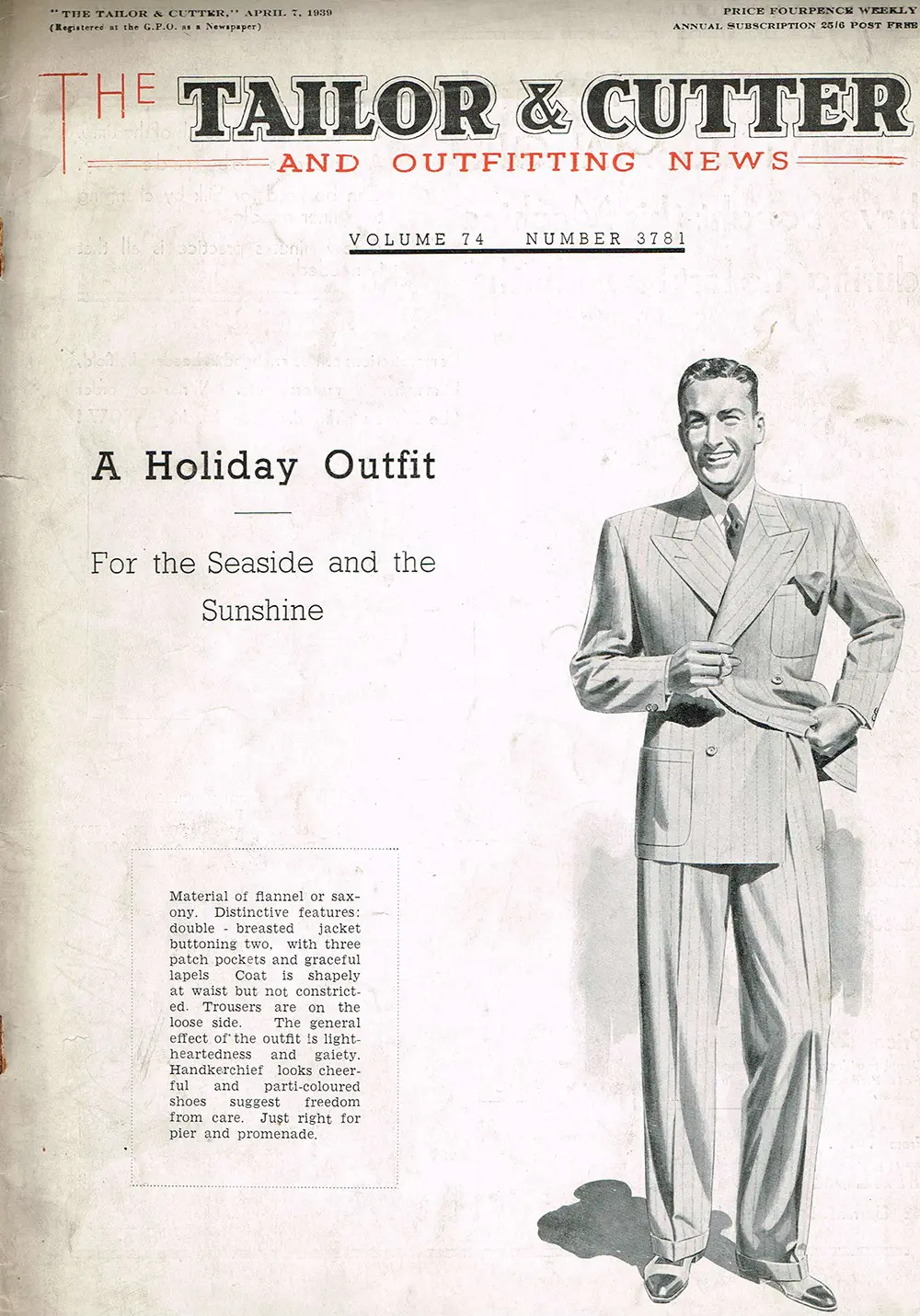

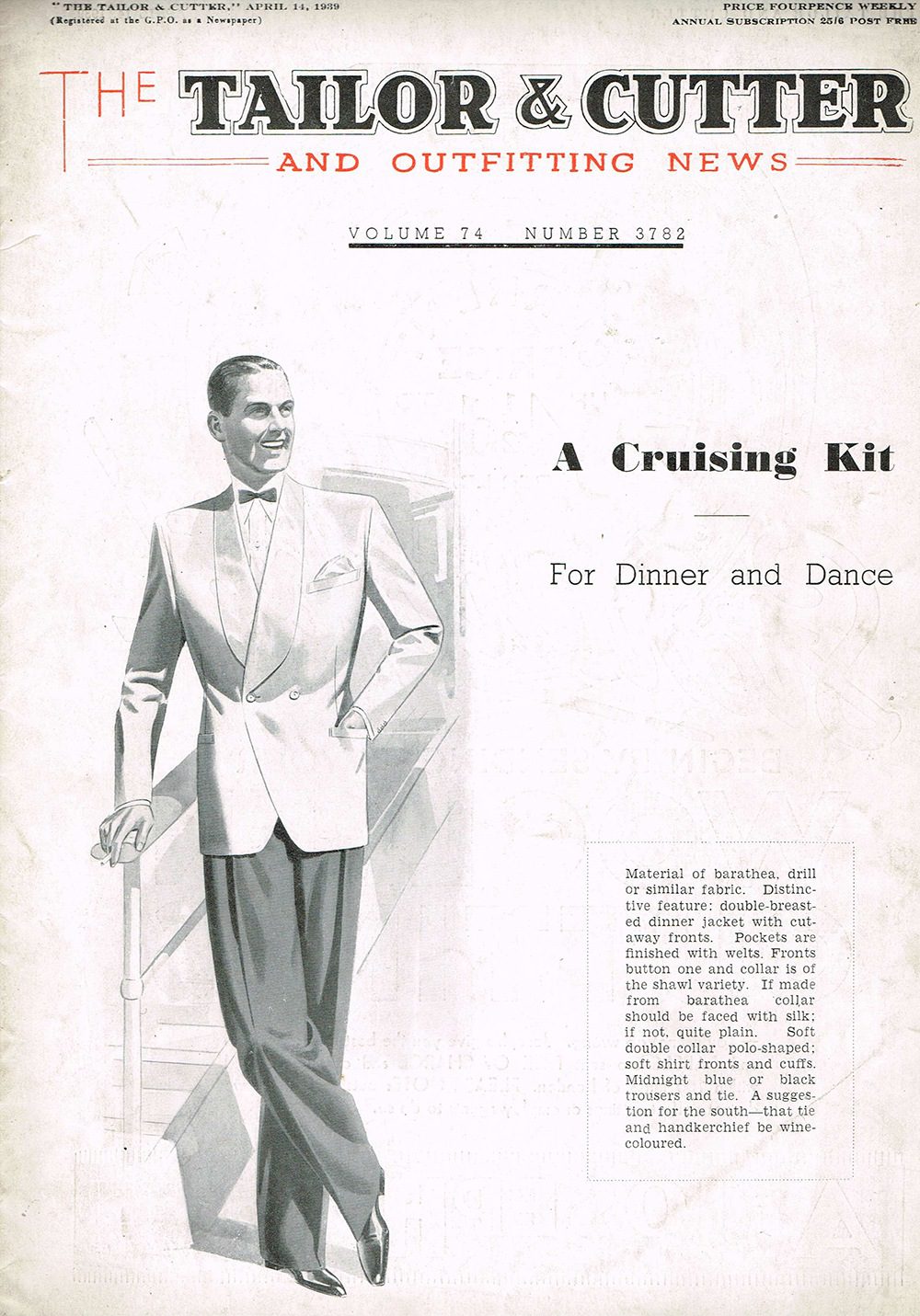

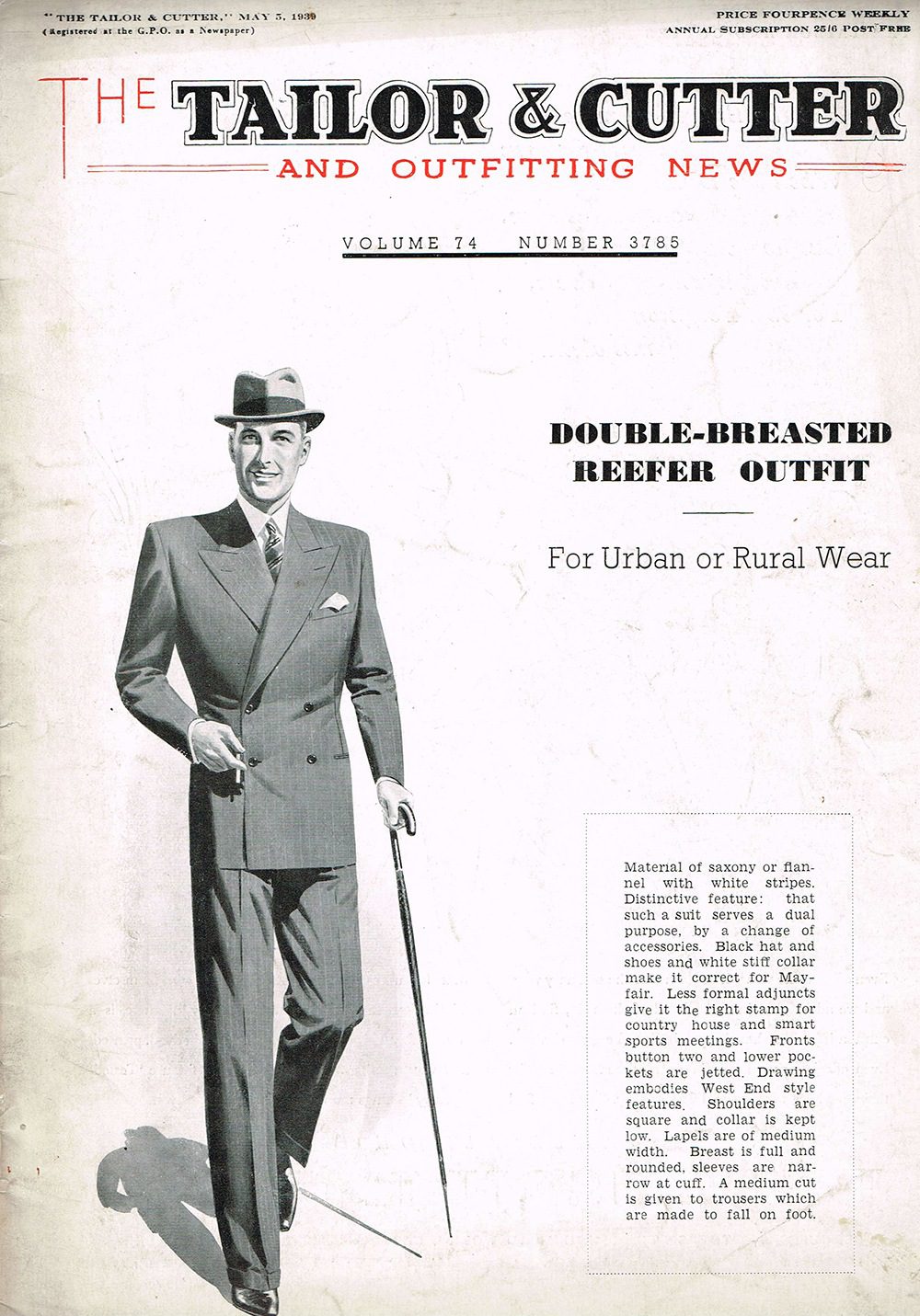

The Tailor & Cutter, the industry’s one-time bible, saw its circulation drop so low it had to close during the 1970s. And tailoring contests, popular since one gentleman (in 1811) won 1,000 guineas by having the wool of two sheep turned into a suit by sunset, went with it. The bottom line today is that it’s impractical to have a street full of tailors – no Italian city, for instance, has them all congregating. But Savile Row is an institution with a village-like atmosphere. The tailors of Savile Row are an elite, both because they’re so few, but also because they’re so good.

Besides, the history of Savile Row has been one of adapting to survive. Even when the area was set in its present lay-out and the road acquired its current name – the first recorded use of “Savile Row” was in the Daily Post of March 12th, 1733 – it was still not a place for tailors. Indeed, while it became a popular residential spot for nobility and high-ranking military men (who were better placed to take advantage of the later opening hours), it was more the precursor to Harley Street, with the leading medical men of the time gathering there to do their own kind of cutting and stitching.

Map of Savile Row and the surrounding area

Tailors of the area were more typically situated a block away, in Cork Street. It was the dandy and pioneer of modern menswear Beau Brummell who took his money – and that of the beau monde that he so influenced – to Cork Street, made the tailors work their imaginations, encouraged others to the area (notably on Bond, Conduit, Princes, Hanover and Maddox Streets) and, by 1806, demand among London’s social elite was such that the first tailor was established on Savile Row.

Meanwhile, the Prince Regent’s building on Regent Street (as a more convenient route for his journey from Carlton House to his villa) created an artificial but all too real division between the tailors of Soho and those of the Row. It established the latter as the place to go – the centre of craftsmanship, of masters and their seven-year apprenticeships – while the former was deemed the place of so-called Slop and Show shops “where gents buy their cheap and nasty clothes”, as one critic had it. Even today a suit from the former will cost half that of one fitted on the Row, even if made by the same tailors.

By 1838, it would have been hard to push a pin between all the tailors who had congregated on Savile Row. Names came and some have since gone: Adeney & Boutroy, John Levick, Brummel’s own tailors, Meyer, and Schweitzer and Davidson. Houses, typically named after their founders, began to develop distinct trademark styles, as they still have today. Their employees would break away to develop further styles and new techniques but always, to maintain credibility, have sited themselves in the locality.

Henry Poole & Co, 14 Savile Row

And credibility the Row certainly has long had. Henry Poole & Co, which was founded by Henry Poole in 1822 and became the tailors to have for the rest of the century, at one point it had over 50 European heads of state or monarchs as its customers. Various houses of Savile Row, with an honourable, old-fashioned gentlemanliness about them, have remained tight-lipped about their celebrity clientele, only releasing the names of their famed customers long after their death – Bing Crosby, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Robert Mitchum and Frank Sinatra among them. Gieves & Hawkes clothed the Duke of Wellington as well as Lord Nelson and Captain Bligh.

Fred Astaire bought at Anderson’s: “It was difficult not to order one of every cloth that was shown to me, especially the vicunas,” he recalled. “They never wore out. I outgrew most of them.” Indeed, Astaire, something of a 20th century Brummel who famously dictated that looking too new was one of the worst sins a well-dressed man could make, would have his chauffeur jump up and down on his fresh suits before he would wear them. The Duke of Windsor would have his suits made by Scholte, a pioneering tailor. Or at least the jackets. Scholte refused point-blank to make the new Oxford bag trousers for his royal patron, considering them ungentlemanly. But, when pushed, Scholte would sell him the cloth so he could have them made up in New York, a procedure he followed until his death.

Times have not been easy for the Row, even if circumstances – be those of fashion, property or economy – have always pushed Savile Row into evolution. Savile Row’s gradual decline may have set in during the 1950s, when quality, accessible ready-to-wear suits, launched by Burton’s, became a serious contender to bespoke. Then there were hundreds of firms operating in the Savile Row vicinity. By 1980 there were 50. Now there are perhaps 20. Yet new blood has always provided a riposte, reminding tailors that suits, however crafted, must be right for the times.

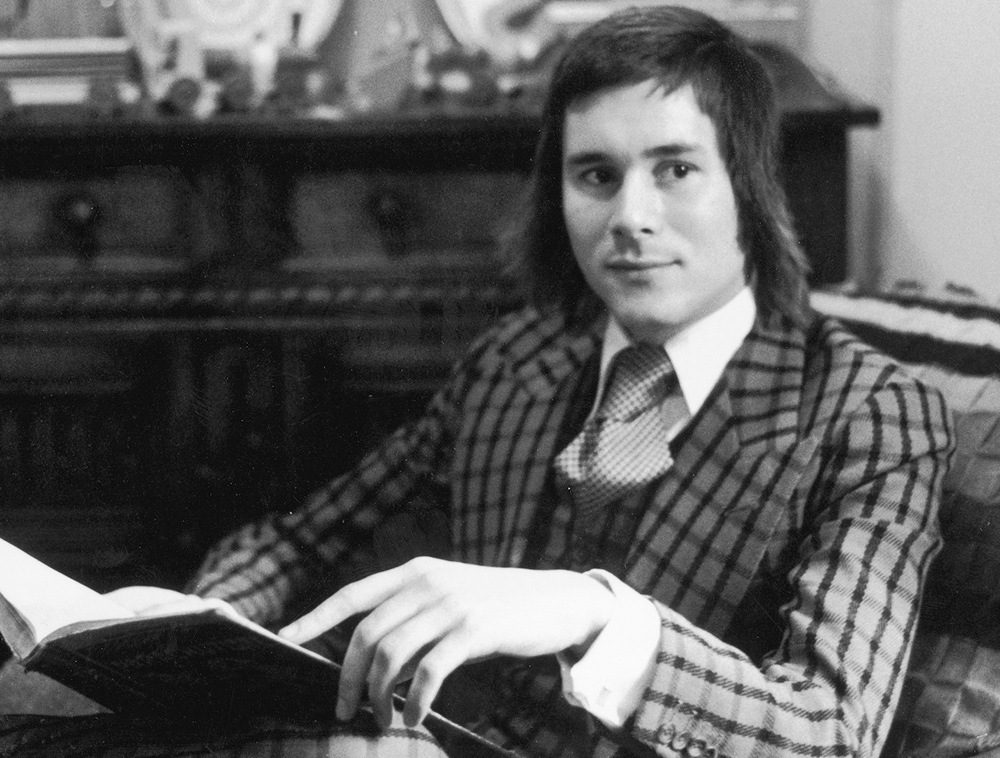

Tommy Nutter

During the 1960s it was provided by the likes of Kilgour-trained Tommy Nutter – a man who knew how to make one striking look, wide lapels and even wider shoulders of 1930s Hollywood, go a long way – and Douglas Hayward, a man whose East End roots may have led him to be somewhat shunned by the Row’s top brass, but whose fresh approach led the faces that defined the era – Terence Stamp, David Bailey and Michael Caine – to his door. Indeed, Hayward made the suits for Caine in The Italian Job.

This was a pattern that would be repeated in the 1990s: Richard James and Oswald Boateng (with the likes of Timothy Everest and Charlie Allen operating off-Row), brought a similar much-needed adrenaline injection to a craft which was threatened, both by the inevitable dying out of its hardcore customer base and the sheer status appeal of lifestyle super-brands such as Gucci and Prada.

Henry Poole & Co bespoke suit, first fitting

It’s thanks to this periodic injection of new blood (as well as a readiness among the old guard to adapt) that means the Savile Row bespoke suit, thankfully, looks as good as ever. While Savile Row may soon no longer be a place where suits are actually made – much of its production is outsourced to other parts of London, if not further afield – its heritage as a place where men of standing, taste and several thousand pounds go to be outfitted lives on, and this in times of more casual dressing and excellent ready-to-wear.

But excellence remains its byword. Thankfully that now comes in a less militant form than that of Louis Stanbury, one of the founders of Kilgour and known for stamping on his employee’s jackets to express his disapproval of any poor workmanship. “Er, yes,” said one suitably impressed customer, “but what about my watch? It’s in the pocket…”